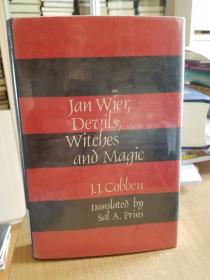

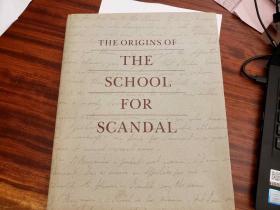

Jan Wier, devils, witches, and magic

现代精神病学之父,文艺复兴医生Johann Weyer (1515-88),极度罕见;现货!非代购!非“海外库房”发货!

¥ 722 八品

仅1件

浙江杭州

认证卖家担保交易快速发货售后保障

作者J. J Cobben (Author)

出版社Dorrance

ISBN9780805922776

出版时间1976

装帧精装

尺寸22 × 15 cm

页数218页

上书时间2024-11-26

- 在售商品 暂无

- 平均发货时间 1小时

- 好评率 暂无

- 店主推荐

- 最新上架

商品详情

- 品相描述:八品

- 图书馆藏书,几年也看不到一本的善本书。

- 商品描述

-

Johann Weyer (in Latin, Wierus; in Dutch, Wier) was born in 1515 at Graves in the Low Countries. His father was a wholesale trader in hops. He was trained as a physician and influenced by both scholarly humanism, represented by Erasmus, and its more mystical side, in the person of Agrippa von Nettesheim, who was Weyer's master when he was an adolescent. Weyer later rejected neo-Platonism and alchemy, although he defended Agippa from personal slurs. He was educated at the University of Paris, arriving in 1533, a year after Vesalius, whom he probably knew and whose works he cites. He finished his education at the University of Orléans, graduating in 1537. He then was employed as town physician at first Ravenstein and then Arnhem. In 1550, he was appointed personal physician for the tolerant Duke William V of Cleve, Julich, and Berg, whose family had progressively reformed religion in the duchy under the influence of Erasmus. Weyer wrote De praestigiis daemonum (1563) while in that position and remained with Duke William V for the next thirty years. He is often described as a Lutheran, although it is difficult to see on what evidence. It seems more appropriate to describe him as a tolerant Erasmian, although his brother Matthias was a spiritual Anabaptist. He remained the duke's physician until he handed over the post to his son, Galenus, and died while attending the duke of Tecklenburg, at the age of seventy-three.

A Divided Image

In standard psychiatric histories, Weyer has been represented as "the father of modern psychiatry," a heroic figure some 400 years ahead of his time: driven by a compassionate humanism and a desire for the truth, he systematically demolished an ideology that preyed on deluded women. He did so with deference to theological authority, however, taking care to support himself with a Biblical literature review and using demonological terms as a kind of shorthand for illness, suffering and mental disorder. His devastating arguments evoked a heated response and inspired future generations of sceptics, who eventually succeeded in crushing the witch hunts. Carl Binz promoted this view in the late nineteenth century, as part of the construction of psychiatry as a discipline, and Gregory Zilboorg is the classic exponent, but it is still widespread. It is true that Weyer's work was known to Charcot and Freud, probably influencing the latter, but this view entails ignoring much of what Weyer said about demons and turning his remarks about a few crazed women into a general statement about all the cases.

To social and intellectual historians, however, Weyer is a very different man, an anti-Catholic polemicist who was nevertheless fascinated by demonology; Weyer actually assigned more power to the Devil than his witch-burning adversaries ever had. The extent to which his work participated in traditional demonological discourse, and was received by readers as such, is clearly indicted on the title pages of the German editions of his book. [see below] His style of argument, while occasionally incisive, was characteristically illogical, contradiction-laden, and myopic. Weyer's case was so weak that the opposition was astounded when he dared to republish it; their response demolished his contentions, and

the net result of his efforts was to exacerbate an already tense situation. Towards the end of Weyer's life, Duke William reinstituted trial by ordeal and torture in witchcraft cases. Stuart Clark, in the course of his massive study of demonology, Thinking with Demons, offers excellent and balanced examinations of both Weyer and his opponent, Jean Bodin. See also Christopher Baxter's essays on both Weyer and Bodin in Anglo's The Damned Art.

— 没有更多了 —

以下为对购买帮助不大的评价