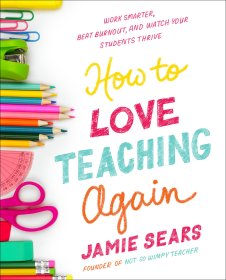

【预订】Reckless

书籍内容简介可联系客服查阅,查书找书开票同样可以联系客服

¥ 128 ¥ 128 九五品

仅1件

作者Chrissie Hynde

出版社Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group

ISBN9781101912232

出版时间2016-08

装帧平装

定价128元

货号YB-86048

上书时间2024-06-29

- 最新上架

商品详情

- 品相描述:九五品

- 商品描述

-

商品简介

Chrissie Hynde, leader of the Pretenders, is one of the most widely imitated figures in rock: sexy, unflappable, vulnerable yet tough, a groundbreaking songwriter and performer. In these pages, Chrissie gives us her story. We see her all-American 1950s childhood in Ohio, and her teenage self falling for the rock music of the 1960s. We follow her to London, where she takes a job with NME and makes her way into the churning ’70s London punk scene, meeting Lemmy, Sid Vicious and Iggy Pop, living in squats, writing songs, playing in early versions of the Clash and the Damned. Her work with the Pretenders—which melded punk, New Wave, and pop to irresistible effect—would catapult her to instant stardom. Through it all is Chrissie’s unmistakable voice, ringing with fearless emotional honesty, a razor-sharp wit, and an enduring belief in the power of rock’n’roll.

伪装者乐队的领军人物克丽丝·海德 (Chrissie Hynde) 是摇滚界最受模仿的人物之一:性感、镇定、脆弱但坚韧,是一位开创性的歌曲作者和表演者。在这几页中,克丽丝向我们讲述了她的故事。我们看到她在俄亥俄州度过了 20 世纪 50 年代典型的美国童年,以及她青少年时期迷恋 1960 年代摇滚音乐的情景。我们跟随她来到伦敦,在那里她在 NME 找到了一份工作,并进入了动荡的 70 年代伦敦朋克场景,遇到了 Lemmy、Sid Vicious 和 Iggy Pop,住在一起,写歌,玩早期版本的 Clash和该死的。她与伪装者乐队的合作——融合了朋克、新浪潮和流行音乐,产生了不可抗拒的效果——使她立即成为明星。贯穿这一切的是克丽丝明确无误的声音,充满无畏的情感诚实、敏锐的智慧以及对摇滚力量的持久信念。

作者简介Chrissie Hynde is a singer, songwriter, and guitarist, best known as the lead singer and songwriter of the enduring rock band The Pretenders. Hynde released nine studio albums with The Pretenders, beginning with 1980’s Pretenders, which Rolling Stone called the #13 Best Debut Album of All Time. Most recently, she released her first solo album, Stockholm, in 2014. She lives in London.

www.chrissiehynde.com

精彩内容

1

Beautiful Trees

The first thing I think of isn’t the rubber tires or cars or factories--it’s the trees, and they will always be my lasting impression of it.

The first one I saw was the cherry tree. It was expecting me. Trees have personalities, subtle but a baby can tell. The house on Hillcrest Street stood on the crest of a hill paved with red bricks. When a car drove up it made a distinctive sound like a Spaniard rolling his Rs. I loved that sound and I loved that house painted blue, the color of choice for an Akron house, with its covered porch you could sit on when it rained. And I loved the pond in Uncle Harry’s backyard next door. But mostly I loved the cherry tree.

Melville and Dolores; Bud and Dee; Mr. and Mrs. M. G. Hynde. Akron, Ohio; Rubber City; Tire Town. Those were the different names of my three parents: father, mother, hometown.

Father: blue eyes, Marine Corps uniform, playing a harmonica. He held me aloft so high I could have touched the ceiling. Mother: perfect nails, Elizabeth Taylor hair, red-and-white striped dress, impeccable. Hometown: streets, trees, streams, the Ohio seasons. I learned everything I needed to know from the three of you.

My mother was from Summit Lake. Her dad, Jack Roberts, was an Akron cop. Her mother, Irene, a seamstress, played piano in the church, Margaret Park Presbyterian. It was to her house on Hillcrest Street where they took me from People’s Hospital that day in September 1951.

Summit Lake was Akron’s Coney Island, the place for boats and rides and summer pastimes--and that’s where Bud and Dolores starting seeing each other. They were bound to meet because his sister Ruth had married her brother Gene.

In later years, my dad spent many hours researching the Hynde family tree. He even trawled through the family records in Edinburgh’s town hall after I married a Scotsman. (Yes, there’s my dad wearing a fishing hat, Bermuda shorts and Hush Puppies, wandering the cobbled streets, always looking up.) “Scotland--Home of Golf,” as said on the tea towel I gave him that he displayed above his workbench in the garage where he crafted his own golf clubs, listening to the police band on his radio.

“Oh, Bud, why are you listening to that?” My mother, critical of any hillbillyish behavior.

“Now, Christy, do your neighbors know you’re Scots?” he asked loudly, every time he came to London. “They don’t care, Dad. They’re Greek.”

The family heritage fad for families started in the seventies. Before that, if you weren’t part of an ethnic minority like African, Italian or Jewish, you were simply American. There were no Hispanics or Asians around, not up north. We looked and sounded like the characters in cowboy shows on TV: Have Gun--Will Travel; Tombstone Territory; The Rifleman. (I knew all the theme songs.) White Europeans: we owned the joint. I must have been fifteen before it occurred to me to ask where the Hyndes came from. And the Craigs, the Roberts and Joneses. According to my father “they,” as in “we,” had come from Scotland via Nova Scotia. His theory: “Now, Hynde was originally spelled H-Y-N-D--the E was added as a flourish!”

(Most of his sentences began with “now.”) I think the “flourish” referred to the florid style of script they wrote in back then. I must have heard him say that fifty times.

My mother’s people were from Caerphilly, and must have found jobs in the coal mines of southern Ohio, as Welsh coal miners would have. “Wales? Where the heck is that? Is that a country?” I asked. Her mother, Irene, had been adopted along with her brother and sisters, Edna, Glovina and Louie. I never knew why; I forgot to ask my mother when I had the chance.

My maternal grandparents, the cop and the seamstress, divorced. I never asked about that, either. It was uncommon to divorce back then. My mother wouldn’t have talked about it anyway. There’s a lot I never knew, I suppose, like with every family.

Before she married she went to New York City to work as a model. I never appreciated how bold that was for a girl back then. It was the “Land of Opportunity,” but people like mine didn’t get very many back then. Now I see that’s where her sense of glamour came from. Always ultramodern. Then she became the wife and mother she was born to be, like every woman in her community.

When I was eight she went back to work, as a secretary, but she always made dinner and did the housework. I wasn’t allowed to come to the table in bare feet. She ran a tight ship.

Grandma Roberts was living with us when she died. She moved in with us on Stabler Road, leaving the little apartment in North Hill where she’d been on her own since the Hillcrest days. I was ten when she had a heart attack at the dinner table. An ambulance came and took her away, and we never saw her again. The thing that shocked me most was my mother saying, “Oh, God. Oh, God.” I’d never heard her talk like that before. Was that swearing? No, it couldn’t have been. We weren’t allowed to swear.

My grandma Hynde was the last one of their generation. She spent the end of her days in an old people’s home playing bingo. We always went to her house in Tallmadge for Easter and would spend the day with Aunt Ruth and Uncle Gene and our double cousins, Dave, Dick and Marianne, all five of us sharing both sets of grandparents. No, that wasn’t a hillbilly thing. Not if my mother had anything to do with it.

Grandma Hynde listened to the baseball game on the radio and did crossword puzzles as good as anyone. By then, Americans were starting a new trend: not to have aging parents live in the family home. It wasn’t the modern way.

My brother, Terry, played clarinet. Kids in the neighborhood called him Benny after Benny Goodman. Then he moved on to the sax and became as fine a sax player as I’ve ever heard. He was the musician of the family, not me. The only time I ever saw Terry star-struck was when I introduced him to Neneh Cherry. “Her dad’s Don Cherry!” Terry could hardly speak.

I had no concept of life beyond Akron’s leafy borders--the warehouses, factories, valleys, streams and woodlands, with their dramatic transformations. For all I knew every town had red brick roads and every fourth house was painted blue.

That’s when Akron was the center of the universe.

Thirty years earlier, Akron and Washington, DC, had been the fastest-growing cities in the nation. Akron was the rubber capital of the world and we had all the major factories--Goodyear, Goodrich, Firestone, General, Mohawk, Ace--and Washington had the White House.

Almost everyone had a job in one of these factories, including my grandpa (Leonard) Hynde, who worked for Goodyear Tire & Rubber. Hundreds of West Virginians moved up to Akron to get jobs as rubber workers, so many that it was often referred to as the capital of West Virginia.

When you walked down Main Street in Akron you either caught the fragrant whiff of rolled oats from the silos at the Quaker Oats factory or the acrid smell from one of the rubber factories. The latter, the distinctive pong like you get patching out in a hot rod, will still conjure to an Akronite the days when the city was the famous Rubber Capital of the World. We were big and important, renowned for rubber and the Soap Box Derby, which took place every year, kids from across the nation submitting their custom-built racers, one of which would soar downhill faster than the others and claim the trophy to national acclaim.

We had industry and abundant, rolling farmland for hundreds of miles to the south, east and west. (See how proud I am?) The Seneca Indians named it “Ohi-yo,” meaning, “It is beautiful, beautiful river.” Yes, Ohio: so be

— 没有更多了 —

以下为对购买帮助不大的评价